The Challenge Set

1962 - 1967: The relentless march of progress and the human price paid...

As 1962 rolled around, the Soviet and American teams were joined by a third in putting satellites into orbit, when in March the Soviet scientists put Kosmos 1 in orbit with the new R-12 rocket, followed by the UK's Ariel 1, sent by on-board American Thor-Delta rocket. The Americans though had their sights set on loftier goals, and on August 27, after the unsuccessful launch of Mariner 1, successfully launched Mariner 2 aboard an Atlas series rocket. Four months later, on December 14th, it became the first man-made probe to reach another planetary body, coming within 21,607 miles (34,773 km) of Venus. Its instruments sent back the first detailed information on another world, sensing temperatures, radiation, magnetic field data, as well as data on the solar winds. Similar plans were in place for a visit to Mars, planned by the Soviets. However, Mars 1 failed en route after five months, and the next two attempts failed to leave orbit.

Whilst things may have been going well on both sides with regards to space, the Cuban Missile Crisis in October only went to prove how fragile the political situation was.

Slowly but surely, the US was starting to retake the lead. As time marched on and the US-made Atlas and Saturn I series of rockets performed the role of putting objects and people into space for the Americans though, Wernher von Braun was looking towards a new generation of rocket; one with enough power to send man to the moon and back. And he wasn't the only one, as 7,000 miles away, Sergei Korolev was looking towards the same prize.

Korolev however, was starting to fall ill. He'd suffered his first heart attack in 1960, and during his time being treated, had also been identified as suffering from a kidney disorder; a legacy of his time as a prisoner in the Gulag. He was warned by his doctors that if he continued to push himself as hard as he had been, that his body would not last much longer. Korolev however had become convinced that Khrushchev saw the space program purely as a propaganda tool, and, fearing its cancellation if it didn't continue to perform that function, he had continued to work with incredible fervour. Now, his health problems started to mount up. A bout of intestinal bleeding saw him rushed to hospital again.

His problems weren't just physical either. In 1961, Vladimir Chelomey, head of OKB-52 (another internal bureau, tasked with research and development of cruise missiles) had been busy working on a massively over-powered ICBM. His proposed new rocket design was to use the Valentin Glushko designed RD-270 engine, which had massive power. This engine would allow the construction of a much simpler rocket design, which Chelomey named the UR-500, and later the Proton. The Proton needed money and political will to fly though, and Chelomey had managed to secure both: he'd started employing members of Khrushchev's family.

Chelomey isn't just working on the Proton though - his satellites Polyot-1 and Polyot-2, launched by Korolev's R-7 rockets in 1963 and 1964 are capable of changing their own orbits, something Korolev hasn't managed yet.

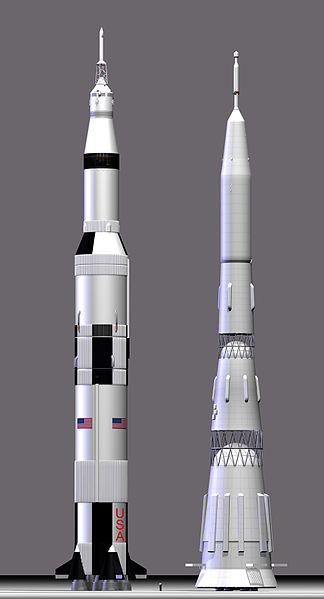

By the early 60's, activity across the Soviet bureaus and NASA was growing at a frenzied pace. Designs were well under way on all sides for systems to take a man to the moon. The chosen concepts created to respond to the challenge though couldn't have been more different.

Laying the Groundwork

The challenge was, in principle, simple. Generate enough thrust to send a craft big enough out of the Earth's orbit. That meant doing one of two things - creating a few huge engines, or many smaller ones. Smaller engines were easier to build and test, but the greater number increased the likelihood of failure. Large engines means less engines to go wrong as long as they work, but getting them to work at all will be a herculean task. Compared to the construction of these rockets, the the vessels used for putting Sputnik and Gagarin in to space look simple. And it's not as though the teams are only working on the moon rockets - at the same time, with the launch of Mariner 4, the Americans managed what the Soviet Mars program failed to: conduct a successful fly-by of Mars. Later the same year, the US-made Ranger 7 returns high-resolution photos of the lunar surface.

To solve the problem of going to the moon though, NASA have decided to go with what they knew, albeit on a vast scale - fewer engines, but bigger.

Much bigger.

Mind-bogglingly bigger.

Five massive engines, each one capable of creating the thrust of an entire Atlas rocket. Each one would weight around 18,500 lb (8,400 kg), stand 19 ft (5.8 m) tall and 12.3 ft (3.7 m) wide, and be capable of burning 5,683 pounds (2,578 kg) of oxidizer and fuel every second to produce an unimaginable 1,500,000 lbf (6.7 MN) of thrust, creating exhaust gases reaching 5,800 °F (3,200 °C).

It wasn't just the engines that were vast either. The rocket they'd power, the Saturn V, was so huge that even if they could build it, there was nowhere to assemble and launch it. Until now, all rocket launches and testing had been done at Launch Operations Center (LOC) at Cape Canaveral. Saturn V was planned to be 363 ft (111 m) tall though, and weigh 6,540,000 lb (2,970 tonnes). Further, the rocket was designed to be assembled vertically, which would need a hanger big enough to do so, along with a track to allow it to be transported entire on a mobile platform to a launch pad. There was no way to realistically adapt the Canaveral facility, so the decision was made to build a new LOC adjacent to Cape Canaveral on Merritt Island. Construction began in November of 1962.

The effect on the area was incredible. People flooded in, with space-related industries immediately repeat the benefit of the billions the American government threw at them. Coco beach became the playground of those around the area. The attitude of the time was work hard, play hard. It came to have some of the highest rates of divorce, sexually transmitted disease, drug use and alcoholism in the State of Florida. Indeed, the locals who supplied the enormous quantities of tranquillisers and sleeping pills used by those working on the space program, could tell when a launch would be to within 72 hours, even if nothing had been announced publicly, such was the massive increase in use of drugs sold prior to launches. The work was non-stop and never ending, with huge finance, massive political pressure and ground-breaking engineering creating a cocktail of pressure many relieved any way they could.

In something that would become a theme for this period though, the new LOC wasn't named until tragedy struck. Almost exactly a year later while travelling with his wife, Jacqueline and the Texan governor and his wife in the presidential limousine on Dealey Plaza, Dallas, Texas, President Kennedy was assassinated. He'd been to oversee the construction just a week earlier. The now President Lyndon B. Johnson, under Executive Order 11129, named the new LOC in Kennedy's honour.

Designating Certain Facilities of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and of the Department of Defence, in the State of Florida, as the John F. Kennedy Space Center

Whereas President John F. Kennedy lighted the imagination of our people when he set the moon as our target and man as the means to reach it; and

Whereas the installations now to be renamed are a center and symbol of our country's peaceful assault on space; and

Whereas it is in the nature of this assault that it should test the limits of our youth and grace, our strength and wit, our vigor and perseverance qualities fitting to the memory of John F. Kennedy;

Now, Therefore, by virtue of the authority in me as President of the United States, I hereby designate the facilities of the Launch Operations Center of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the facilities of Station No. 1 of the Atlantic Missile Range, in the State of Florida, as the John F. Kennedy Space Center; and such facilities shall be hereafter known and referred to by that name.

Lyndon B. Johnson

The White House,

November 29, 1963

The order joined both the civilian LOC and the still military-operated Cape Canaveral both under the designation John F. Kennedy Space Center, which had the unintended effect of creating a certain amount of confusion for the public. NASA Administrator James Webb clarified this by issuing a directive stating the Kennedy Space Center name applied only to the LOC, while the Air Force renamed the military site Cape Kennedy Air Force Station.

Engineering the Future

The only upside to the challenge posed by getting the Saturn V in to space was that these engines would only be needed for the first stage. The second and third stages could be powered by a much smaller engine, which could also be used on other rockets. For that, Rocketdyne (who would also build the Saturn V main engines) created the J-2 engine, which would also see service as the main engines for the Saturn IB rockets.

As for the Saturn V engine though, every single challenge faced in making such an engine was hard. The US Air Force had started work on an engine of the required size as far back as 1957, but eventually development after they realised there was nothing they could want that would require so much thrust. NASA, on the other hand, knew exactly what it would be useful for, and so contracted Rocketdyne to complete the development of what they'd named the F-1. The first static firing of the full engine had been performed in March 1959, but all had not gone well. The engine suffered from serious combustion instability problems, by which pressure waves would form in the combustion chamber. These could build and catastrophic failure, and destroy the entire engine. A problem, when von Brun needed five working flawlessly.

Eventually, the engineers at Rocketdyne had come up with an interesting way of working on the problem. They attached small C4 charges to the outside of the combustion chamber and set them off while the engine was firing. This allowed them to simulate the conditions of the vibrations produced, gathering data more safely and learning how to control the resonance. Eventually, they produced injector designs which were so stable, they could stop the charge-induced instabilities within 0.1 of a second.

The first engine was delivered to NASA for suitability and performance testing in October 1963, and more than a year later, in December 1964, it was certified for use. In the Rocketdyne F-1, von Braun had found his engine. Now he just needed a rocket which could handle it.

Back in Soviet Russia, records continued to be set. This time it was the turn of Valentina Tereshkova, who would become both the first woman and civilian into space, on Vostok 6. Korolev however continued to suffer from further ill-health. He had had been diagnosed with cardiac arrhythmia, and soon after, inflammation of his gallbladder. Meanwhile, Khrushchev was deposed from power.

Moreover, Chelomey had become Korolev's main internal competition. He'd proposed an alternate to the moon landing mission, with much lower risk. Instead of sending men to land on the moon, he suggested a series of lunar orbit missions, which would be less challenging, and have a greater chance at beating the US. Politics in the Soviet Union continued to be troubling though, with a military reluctant to support what was seen as a political propaganda campaign, without an military benefit. Despite this, Korolev and Chelomey both still pushed for lunar missions.

With Khrushchev's departure though, Chelomey lost his advantage. The Chelomey and Korolev teams continued to fight for funding and support, until the new leadership grew tired of it. In 1965, after a year of turmoil, the Soviet leadership stepped in and commanded a compromise. A circumlunar mission would be launched, sent with Chelomey's Proton rocket, but using Korolev's Soyuz spacecraft rather than the Zond design Chelomey's team had created. That mission would aim for a launch in 1967, in time for the 50th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. In the meantime, Korolev would continue on the N1 project, despite not being given the funding he needs. Glushko proposed the RD-270 engine for the N1 project, but Korolev was unwilling to use an engine with the propellant the RD-270 used, which was unbelievably dangerous, even for rocket fuel. Glushko on the other hand stated that it was both unrealistic and unfair to expect him deliver a similar engine in such a short period of time, when there was practically no money, primitive computer technology and inferior kerosene fuel which didn't burn as cleanly as the American rocket-grade kerosene used by the F1. Further tensions led to him refusing to work with Korolev in general. He left the N1 project to work with Chelomey on the Proton designs.

In the meantime, under Korolev, OKB-1 teams continue work on smaller projects. On the 18th March 1965, Alexey Leonov became the first man to walk in space, whilst on the Voskhod 2 flight. Leonov exited the craft, and stayed outside for 12 minutes and nine seconds, whilst connected by just a 5.35-meter tether.

At the end of the spacewalk though, whilst trying to re-enter the Voskhod 2, Leonov ran in to problems. His spacesuit, no longer contained by the air pressure of an atmosphere or the air of the ship, had inflated like a balloon, forcing him to return through the hatch head-first. Having done so though, he was faced with a second problem - the suit's continued size meant he was unable to turn around to close the outer hatch, nor to push himself back out to re-enter correctly. Using a release valve to manually vent air, he managed to reduce the pressure. After a tense moment, he managed to deflate the suit enough turn around and bend to close the hatch again. The incident was covered up at the time, and only later be revealed how close Leonov came to being stranded in space.

The problems didn't end there though. With only five minutes before they were scheduled to begin reentry to return home, Leonov and his crew mate, Pavel Belyayev, discovered that the automatic guidance system wasn't functioning. As a result, they would have to fly the spacecraft manually. To make matters worse, they were now dangerously low on fuel. As they began their reentry, things got still worse. In a replay of the Gagarin mission, the orbital and landing modules had stayed connected by a communications cable. The craft spun together until the cable burned through in the intense heat, allowing the craft to stabilise, finally coming to land in deep snow in Solikamsk, just outside Siberia, wedged against a birch tree which prevented the two men from getting out. Unable to be rescued that night, a helicopter pilot threw them supplies to wait out the night in temperatures that fell down to -22 °F (-30 °C). They were collected the next day, and reported their mission. Leonov said simply:

Provided with a special suit, man can survive and work in open space. Thank you for your attention.

It's not hard to guess what his feelings on the last few days had been.

An Ambitious Plan

In order to have any chance at building his rocket, Korolev needed an engine supplier. He turned to Nikolai Kuznetsov, a fairly inexperienced rocket designer, who developed the NK-15 and NK-15V engines for the project. It was an incredibly ambitious design. Whereas the Saturn V was to have five F-1 engines in its first stage, a further 5 smaller J-2 engines in the second and a final J-2 powering stage three, the N1-L3 was to have a more.

A lot more.

The first stage alone had 30 NK-15 engines, 24 in a ring around the edge, and another six closer in. These together produced even more thrust than the already colossal figures of the Saturn V; a full 36% more. The second stage consisted of another eight NK-15s arranged in another ring, whilst the third carried four NK-21 engines. In total, Saturn V would carry 11 rocket motors. N1-L3 would have 42, all of which would have to work perfectly. For an unreliable engine, it was a huge ask.

As if that wasn't enough, NASA were now surging ahead, launching a manned mission almost every two months. The time spent in space, including setting a two week endurance record for time in space, and practising docking manoeuvres are giving them the experience they need to launch a lunar mission. The Soviet team were falling behind with every month that passed.

| Saturn V | N1-L3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Diameter, maximum | 33 ft (10 m) | 56 ft (17 m) |

| Height w/ payload | 363 ft (111 m) | 344 ft (105 m) |

| Gross weight | 6,478,000 lb (2,938,000 kg) | 6,030,000 lb (2,735,000 kg) |

| First stage | S-IC | Block A |

| Thrust, SL | 7,500,000 lbf (33,000 kN) | 10,200,000 lbf (45,400 kN) |

| Burn time | 2 m 48 s | 2 m 5 s |

| Second stage | S-II | Block B |

| Thrust, vac | 1,155,800 lbf (5,141 kN) | 3,160,000 lbf (14,040 kN) |

| Burn time, s | 6 m 24 s | 2 m |

| Orbital insertion stage | S-IVB (burn 1) | Block V |

| Thrust, vac | 202,600 lbf (901 kN) | 360,000 lbf (1,610 kN) |

| Burn time, s | 2 m 27 s | 6 m 10 s |

| Orbital payload | 264,900 lb (120,200 kg) | 209,000 lb (95,000 kg) |

| Injection velocity | 25,568 ft/s (7,793 m/s) | 25,570 ft/s (7,793 m/s) |

| Earth departure stage | S-IVB (burn 2) | Block G |

| Thrust, vac | 201,100 lbf (895 kN) | 100,000 lbf (446 kN) |

| Burn time, s | 5 m 47 s | 7 m 23 s |

| Translunar payload | 100,740 lb (45,690 kg) | 23,500 kilograms (51,800 lb) |

| Injection velocity | 35,545 ft/s (10,834 m/s) | 35,540 ft/s (10,834 m/s) |

The Fall of a Giant

Korolev had even larger issues though. The Soviet leadership weren't willing to release the funds requested, instead granting his team only half of what they'd asked for. This didn't leave time or money enough to build test facilities. Instead, the decision was taken to test the N1-L3 in the only way they could - by launching it. While it was being constructed, the team also worked on the Soyuz 7K-LOK, a spacecraft designed to be able to carry a crew to the moon, as well as acting as a mothership for an LK lander. If they could get the N1-L3 to work, they might have a shot at beating the Americans. They weren't his only issue though.

The program was running in to problems though. A lack of budget, an overly ambitious design, and a temperamental engine were one thing, but crisis was closer to hand. On the 5th January 1966, he was taken in to hospital for surgery. What happened in the hospital is still disputed, with various accounts stating different things. Whatever the truth though, it didn't go well. His health continued to deteriorate, during his time there.

He died nine days later, aged just 59.

Under a policy instigated by Stalin, which his successors continued, Korolev's identity had been kept a state secret. It was thus only that in death was he finally recognised both by his own people and the world at large for his incredibly accomplishments. His obituary was published in the Pravda newspaper, on the 16th of January 1966, accompanied by a photo of Korolev with all his medals. He man once renounced by his people and sentenced to hard labour was now honoured with a full state funeral in the Red Square, and his ashes interred in the Kremlin Wall.

The High Cost of Progress

Back in America, the desperate race to fulfil the government's command was causing development to run at breakneck speed. In December of 1964, Gemini's 6 & 7 made the first rendezvous in space, eventually coming within 1 ft of each other. Gemini 6 would then go on to land within 10 miles (18 km) of the intended target site, making it the first accurate atmospheric reentry.

Apollo 1 was scheduled to have served as the first manned test flight of the Apollo Command/Service Module (CSM), and was to orbit Earth having been launched atop a Saturn IB rocket. The aim was to test launch operations, the ground tracking and control facilities and the performance of the Apollo-Saturn launch assembly, laying the groundwork for a Saturn V launch. At the same time, the Vehicle Assembly Building, where the Saturn V's will be pieced together, has just been completed.

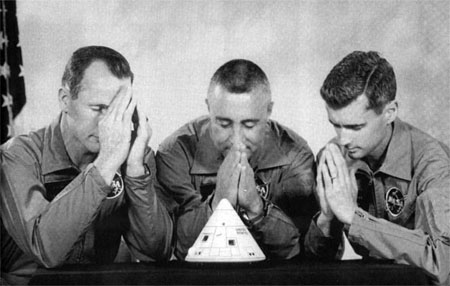

Deke Slayton, who'd been one of the Mercury Seven, had been grounded after it had been found he had an erratic heart rate. Then grounded by the Air Force too, he'd become first unofficially, and then in 1963 officially the Coordinator of Astronaut Activities working as the head of astronaut selection. He had then moved on to become Director of Flight Crew Operations, and selected the first Apollo crew in January 1966. His choices were:

- Virgil "Gus" Grissom as Command Pilot

- Edward White as Senior Pilot

- Donn Eisele as Pilot.

Eisele however suffered from dislocation of the shoulder twice while undergoing weightlessness training, and had to undergo surgery. In response, Slayton replaced him with Roger Chaffee, and NASA announced the crew selection on March 21, with James McDivitt, David Scott and Russell Schweickart named as the backup crew.

At the same time, NASA was examining the idea of conducting the Apollo 1 mission alongside the final Gemini mission, Gemini 12, in November, it soon became clear that the engineering involved would take far too long. Indeed, such was the over-run that the first flight test was moved back to February of 1967. This was not surprising though, given the scale of what was being done. The difficulties faced in creating the Apollo Command/Service Module were far beyond those faced by any module which had been sent up so far. In a spacecraft review meeting held with Apollo Spacecraft Program Office (ASPO) Joseph Shea in August, the crew voiced their concerns with having flammable material in the cabin. It was certainly convenient, but the idea of having something flammable in a pure oxygen environment seemed like a bad idea. Shea however conditionally approved the Apollo design, leading to the crew giving him a portrait after their meeting, bearing the inscription:

It isn't that we don't trust you, Joe, but this time we've decided to go over your head.

Shea gave his staff orders to tell North American to remove the flammables from the cabin, but did not supervise the issue personally. That was far from the only thing to have needed changing though; in total 113 significant planned engineering changes were scheduled to be completed at Kennedy Space Center. Things continued to be developed on-site, leading to a total 623 engineering change orders being made and completed after the module was delivered. Worse, every change had to be reflected in the training simulator, to ensure they astronauts were adequately prepared. As a result of the constant tweaking and interference, Grissom became so frustrated that he took a lemon from a tree near his home and hung it on the simulator. They knew what they were doing was dangerous, and in December he stated while being interviewed:

You sort of have to put that out of your mind. There's always a possibility that you can have a catastrophic failure, of course; this can happen on any flight; it can happen on the last one as well as the first one. So, you just plan as best you can to take care of all these eventualities, and you get a well-trained crew and you go fly.

It was a dangerous mix and something was bound to go wrong.

On January 27th 1967, at 06:30 and 54 seconds local time, it did.

Immediately after the fire, to avoid appearance of a conflict of interest, NASA Administrator Webb asked President Johnson to allow NASA to handle the investigation, according to its established procedure. Webb's Deputy Administrator Robert Seamans then directed establishment of a review board, chaired by Langley Research Center director Floyd Thompson and consisting of eight other experts, including astronaut Frank Borman and spacecraft designer Maxime Faget. The Board issued its final report on April 5. The conclusions were challenging to say the least. More damning though were the words of flight director Gene Kranz. On the Monday morning after the disaster, Kranz called his branch and flight control team to a meeting, in which he expressed the values he attributed to NASA and spaceflight.

Spaceflight will never tolerate carelessness, incapacity, and neglect. Somewhere, somehow, we screwed up. It could have been in design, build, or test. Whatever it was, we should have caught it. We were too gung ho about the schedule and we locked out all of the problems we saw each day in our work. Every element of the program was in trouble and so were we. The simulators were not working, Mission Control was behind in virtually every area, and the flight and test procedures changed daily. Nothing we did had any shelf life. Not one of us stood up and said, 'Dammit, stop!' I don't know what Thompson's committee will find as the cause, but I know what I find. We are the cause! We were not ready! We did not do our job. We were rolling the dice, hoping that things would come together by launch day, when in our hearts we knew it would take a miracle. We were pushing the schedule and betting that the Cape would slip before we did.

From this day forward, Flight Control will be known by two words: 'Tough' and 'Competent.' Tough means we are forever accountable for what we do or what we fail to do. We will never again compromise our responsibilities. Every time we walk into Mission Control we will know what we stand for. Competent means we will never take anything for granted. We will never be found short in our knowledge and in our skills. Mission Control will be perfect. When you leave this meeting today you will go to your office and the first thing you will do there is to write 'Tough and Competent' on your blackboards. It will never be erased. Each day when you enter the room these words will remind you of the price paid by Grissom, White, and Chaffee. These words are the price of admission to the ranks of Mission Control.

Slayton was originally to have been presented with a diamond studded pin, after the Apollo 1 mission. However, after the fire, he was presented with it by the widows of the Apollo 1 crew. Slayton in turn would give the pin the the commander of Apollo 11, Neil Armstrong, who took it with him on the famous moon landing mission, in honour of the three men and their sacrifice.

The High Cost of Progress: Soyuz 1

Apollo 1 wasn't to be the only disaster of 1967 though. With the death of Korolev, Vasily Mishin, a solid engineer who had worked alongside Korolev for years as his right-hand man, was given the role of Chief Designer over Glushko and Chelomey. In his new role, he inherited both the ongoing Proton/Soyuz circumlunar and N1-L3 rocket and lunar landing missions, along with various smaller projects. Only a few months later, he was faced a disaster of his own.

Soyuz 1 was a manned spaceflight, launched successfully into orbit on 23 April 1967 with cosmonaut Colonel Vladimir Komarov aboard. It was the first crewed flight of the Soyuz spacecraft, and to be a solid demonstration of the Soviet's continued lead over the Americans, who were reeling from the Apollo 1 incident, and still a long way from getting an Apollo capsule into space. The mission though was plagued with technical issues from the very start.

The Soviet team had been struggling for a long period, due to budget cuts and the need to try and create a successful rocket capable of travel to the moon. This was therefore to be first Soviet manned spaceflight in over two years. Despite failures of the previous unmanned tests of the Soyuz, and the rockets which would launch it (Cosmos' 133 140), and a third attempted test flight malfunction causing the rocket to explode on the pad, the decision was taken to launch Komarov anyway. Too much time was slipping by, and it was becoming increasingly obvious that the Americans were pulling away. The Soviet leadership needed a solid win.

Prior to launch, Soyuz 1 engineers are said to have reported over 200 design faults to party leaders, but their concerns were overruled. Yuri Gagarin was scheduled as the backup pilot for the mission, and well knew the design problems. In an attempt to save Komarov, the tried to have him bumped, knowing the leadership would not dare risk his life. Komarov refused to pass though, even though he believed it to be doomed. He viewed Gagarin as too valuable, and believed he might be made to fly anyway.

The problems almost immediately after entering space. One solar panel failed to unfold, leading to a power shortage. Then the orientation detectors malfunctioned, and then broke entirely, leaving the automatic stabilization system completely dead, and an only partially working manual backup.

As a result, the flight director decided to abort the mission. 5 orbits later, Komarov fired the Soyuz 1 retrorockets and reentered the Earth's atmosphere. Piloting the broken ship, incredibly, he made it through the atmosphere. To finally slow the descent for landing, first the drogue parachute was deployed, followed by the main parachute. However, the main parachute did not unfold, and when he manually deployed reserve chute, it became tangled with the initial drogue chute, which had not released.

The ship slammed into the ground at almost 90 mph (140 km/h). A rescue helicopter spotted the descent module lying on its side with the parachute spread across the ground. The retrorockets then started firing which concerned the rescuers since they were supposed to activate a few moments prior to touchdown. Komarov was killed on impact, becoming sadly the first in-flight fatality in the history of spaceflight. He would not be the last.

Back to part 2: Man in the Heavens

Continue to part 4: Man on the Moon