Space Stations & Robots

1975 - 1998: Mankind turns his invention from politics to science, creating the Space Shuttle, space stations and probes

The Apollo project is no more. July 1975 has seen the last flight of a Saturn V, ushering in a new era in US/Soviet relations. However, America finds itself in a difficult position - launches to space can depends mainly on the Titan III and Atlas-Centaur. Both work admirably, but aren't re-usable. Work has therefore started on a craft that would be able to entirely reused for every launch. August sees the test of an unpowered, delta-wing craft, proving that landings of such a craft from high speed and high altitude are at least possible. That month also sees America launch Viking 1, which in 1976 became the first probe to land on Mars and successfully complete its mission. It landed on July 20, and continued to operate long past its intended lifespan. In fact, it continued to work up until November 13, 1982, some six years later. Elsewhere though, 1976 was proving to be a year of firsts in another way.

Five years earlier, four companies had been chosen to submit proposals for the design and construction of the shuttle: Lockheed Aircraft, McDonnell Douglas, Grumman and North American Rockwell. In July, due to the design's relatively low and realistic costs, as well as its simplicity with regards to ongoing maintenance, as well as the company's previous experience, North American was selected as the preferred supplier. From the beginning, the design was one of compromise. For example, the solid rocket boosters that sit either side of the main liquid fuel tank weren't NASA's first choice. Whilst they would have performed better and been cheaper to refuel, as well as being more environmentally friendly, the solid boosters which ended up being used were cheaper to develop, and funding was tight.

The final design chosen therefore consisted of a delta-winged orbiter with three conventional liquid-fuelled engines, a large expendable external tank to provide fuel, and two reusable solid rocket boosters. Work commenced on June 4th 1974, and on September 17th 1976 the Space Shuttle Enterprise OV-101 was unveiled. Designed to help refine the design, it would be used to conduct test flights, and as such had no engines, thrusters, heat shield, or radar. Instead of the heat shield, its surface was covered with fake polyurethane foam tiles, and the leading edges of the wings had fibreglass panels, instead of the expensive carbon-carbon pieces used on the final shuttles. Only a few tiles were actually real, for testing purposes.

Nevertheless, even at this early stage, it was still recognisable a shuttle. It had been intended that these parts would be added later, during a retrofit, which would make it the second orbiter in service. However, during the testing of Enterprise, and construction of Columbia, the construction of the fuselage and wings was seriously modified. As a result, making Enterprise space-worthy would have cost more than simply building an entire new orbiter from scratch around an existing test frame.

June of 1977 brought sad news to the space community though, as on Thursday 16th, the world noted the passing of Wernher von Braun. The divisive figure who'd been both part of the SS in Germany and all major NASA programs, inventor of both the V-2 designed to kill, and Saturn V which took man to the moon and brought all mankind together, died of pancreatic cancer. His gravestone notes Psalms 19:1, which reads:

The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands.

In August, two months later America would send arguably its most famous probes in to space, on an audacious mission. The twin Voyager probes weren't originally called Voyager at all. Instead, they were designed to be part of the Mariner program; Mariners 11 and 12 respectively. They were renamed as the Voyager Program however as they were, by this point, so far beyond the original Mariner design that it was felt they warranted a new name.

The Voyager Program was, in concept, not dissimilar to the Planetary Grand Tour. The aim would be to use the rare alignment of the outer planets to visit every single one in turn. The planets themselves wouldn't be in position until later that decade though, giving time to build the probes, work out the exact flight path, and send them. Limited funding at the time had made the Grand Tour impossible, but elements from it were now brought into the Voyager Program.

Voyager 2 was the first to launch. Its trajectory was designed to allow flybys of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Voyager 1 was launched shortly after, with a shorter and faster trajectory calculated to provide a flyby of Titan, Saturn's largest moon, which is larger than our own moon and was known to possess an atmosphere.

In the meantime, whilst Enterprise was being built and undergoing testing, North American had started work on what would become the first shuttle to fly: Columbia. Whilst being built, the information gleaned from the Enterprise test program was being used in her design, so whilst she began construction in 1975, it wasn't until March 25th 1979 that Columbia arrived at the Kennedy Space Center. Shortly before, in January, Voyager 1 made its flyby of Jupiter, whilst Voyager 2 arrived slightly later in July, discovering the planet's rings, as well as the volcanic activity on its moon Io.

July would also see the ending of an era, as NASA controllers positioned Skylab into a stable orbit and shut down its systems. This left the USSR with the only functional, in-use space station, Salyut 6. By this point, crews on Salyut were staying in space for up to six months at a time, with the Soviet crews, engineers and scientists learning more and more about running successful space station operations. The next year would see Voyager 1 make its pass of Saturn, returning the first high-resolution images of the planet, its famous rings, and its satellites. It also made the first flyby of Titan, before heading off out toward interstellar space.

After more testing and refinement, Columbia successfully launched on April 12, 1981, the 20th anniversary of the first human spaceflight (Vostok 1), and in doing so, ushered in a new era of manned spaceflight.

Space Shuttles and Space Stations

1981 would also see Voyager 2 encounter Saturn in August, returning further incredible images of both the planet and its system of moons.

Over the next few years, several other shuttles were constructed, named Challenger, Discovery and Atlantis. Back in the Soviet Union though, the Salyut program continued, with Salyut 7 being launched in 1982. It was the last of what would be considered the monolithic space stations, before the change to the modular based approach still used today. The Salyut series had all been single-piece stations, launched using Proton rockets. With the Space Shuttle, which could both carry payloads and act as a reusable base of operations, there was the option of a new type of American Space Station.

That new type of design was also being considered by a team in the USSR. Having concluded the Salyut series of stations, attention turned to their replacement, as well as the design of a craft that could service the next generation of Soviet space stations. Thus in 1974, at the same time as the US began working on its shuttle, the Buran project was proposed. Despite the ongoing costs of running space stations, and the failed N1-L3, this was to be the biggest financial allocation to development of a program for space travel ever. The Sovet leadership was motivated out of fear; the main concern being that the Space Shuttle could be used for military purposes, due to its enormous payload capacity (up to 30 tonnes for launch and 15 for return), which was vastly greater than previous American launch systems. No-one in the USSR could believe that there could be a civilian requirement for something able to launch such huge amounts in to orbit, which may perhaps have been a failure of vision on their part.

Whilst Buran began work, with designs based of the US shuttle, which had been found to be pretty much the perfect design, work had also begun on a new generation of Soviet space stations. Mir, meaning "Peace", had been commissioned two years later in 1976, with the aim of creating an improved successor to Salyut. Four had been launched at the time, and another three during its development. The initial design was to have four docking ports, two at either end and two on each side of a docking sphere at the front. This would allow the system to be extended over time to add new capabilities. However, by August of 1978, the design had been finalised, and had evolved to a single rear port, with five further ports around a sphere at the front of the station.

In the political arena, there was a belief that having two programs for building orbital stations was and unnecessary expense. As a result, Vladimir Chelomey's Almaz military station program, which had spawned the Salyut series of stations, was now folded in to the Mir program. The docking ports for the new Mir design were therefore altered to allow them to take new modules weighing up to 20 tonnes. This was so the new station could use the resupply vessels designed for the Almaz stations, known as TKS Spacecraft. NPO Energia, the Soviet's main bureau for space work, subcontracted the build of the final design out, being busy with their ongoing work on Salyut 7, the third design of the Soyuz craft, known as Soyuz-T, the work on the resupply-focused Progress spacecraft and the on-going Buran.

As the world waved goodbye to the 1970s, construction began on Buran, which had been finalised in its design. The first full-scale Buran was completed in 1984, after the Soviet leadership decided all available resources should be put into it. It was also the year that marked the passing of Vladimir Chelomey, who's rockets continued their work for the Soviet space program. This effectively halted the Mir program, which only began to receive funding again later that year when Valentin Glushko, now head of NPO Energia, was ordered to put Mir in to orbit by 1986, in time for the 27th Communist Party Congress. To speed work, much of the systems testing work on the Core Module performed was done at the Baikonur Cosmodrome. This was vital work, as the Core Module provided the main living quarters, as well as housing the environmental systems, attitude control systems and main engines. If those didn't work, the Soviets didn't have their station. Having had to abort a launch on the 16th February 1986, due to the failure of the comms system, it was therefore on the 19th, at 21:28 and 23 seconds UTC that Mir was launched by the Chelomey and Glushko designed Proton-K.

Back in America Knowing that the Soviet scientists and engineers were working on Mir, and that the Buran was essentially a copy of the Shuttle, in 1984 now President Ronald Reagan echoed the JFK announcement of the Apollo missions, as in the State of the Union Address before Congress he announced his intention to create America's own station within a decade. This station would act as a repair platform for satellites, an orbiting microgravity laboratory, and an observation post for advancing astronomy. Given the incredibly American name "Freedom", the task of designing such a platform was given to the newly established Space Station Program Office at Johnson Space Center. However, the design work involved would prove challenging, and take several years. They'd also be influenced heavily by possibly the second most famous space-related disaster, which occurred shortly before the launch of the Mir Core Module.

Challenger.

The Challenger Disaster

On January 24, 1986, NASA celebrated as Voyager 2 reached Uranus. In doing so, it discovered no less than 11 moons, and started to study its atmosphere and rings. Meanwhile, Challenger was being readied at the Kennedy Space Center for launch on mission STS-51-L, which was to be both the 25th shuttle mission, and the tenth flight for the Challenger itself. It had been meant to launch that day, but bad weather causted it to be rescheduled repeatedly. Finally, on the 28th, the go-ahead was given.

Forecasts for launch on the 28 predicted a bitterly cold morning, with temperatures down as low as −1 °C (31 °F), which was lowest temperature under which a launch would be allowed. With it being so cold, various of the engineering team of the solid rocket boosters were concerned with launch. The conditions were discussed on a conference call, with the engineers expressing their concerns as to how well the rubber O-rings would hold up. They lobbied for a postponement of the launch until warmer weather, stating that they lacked the data required to know whether the joints would be sealed correctly. The O-rings themselves were vital component, as if they failed, there was no back-up system possible to put in place.

NASA however opposed the delay despite the concerns. The feeling was that it was impossible to have a craft which couldn't launch for several months of the year due to cold. In addition to the concerns of the O-rings, others were afraid that the large build-up of ice on the pad, and on the fuel tank, boosters and orbiter. Some feared ice could be shaken loose during launch and fall to damage the thermal protection tiles on the base of the orbiter, causing it to suffer damage or be destroyed on reentry. Despite the various concerns raised, Houston-based mission manager Arnold Aldrich gave the go-ahead for a launch, postponing only by an hour to give the team time to try and de-ice the shuttle. They'd already worked through the night, and knew there was no way to remove all the ice before launch.

At 11:37 and 53 seconds, the Shuttle's main engines fired up and began burning fuel at incredible speed. 6 seconds later, Solid Rocket Boosters (SRB) ignited. Less than a second later, the right SRB started to fail, with plumes of gas coming from it. These were the result of a joint opening and closing as the booster's skin ballooned under the stress of ignition. The metal bent and superheated gasses jetted out at over 2,760 °C (5,000 °F). Previously when this had happened, the primary O-ring shifted and the heat melted it to form a seal, closing the gap. Now though, the freezing ring didn't move. The heat instead seared into the ring, which took damage. It didn't seal the crack, and the secondary O-ring had been moved out of position as the metal had bent. Instead of sealing, both were vaporised.

Challenger blasted its way clear of the control tower after three seconds, and the engines throttled up, guzzling fuel at a rate of 5 tonnes per second. 25 seconds later it was doing 400 mph (644 km/h). Despite throttling back, 15 seconds after that it blasted its way through the sound barrier. The engines were returned to full power 12 seconds later. At just under 59 seconds in to the flight, the shell of the right SRB started to fail completely, with parts beginning to burst into flame. A moment later the vessel passed 1.5 times the speed of sound. The jet of flame interfered with the handling of the Shuttle. 72 seconds in to the flight, everything went wrong.

The SRB detached from the external fuel tank and Shuttle pulled hard to one side. The tank itself then failed, with the hydrogen and liquid oxygen tanks rupturing, the contents mixing and exploding. A second later, the craft began to break up. Massive g-forces ripped the tank and Shuttle apart, whilst the SRBs flew away. The crew compartment was blasted away and began to fall from the sky.

In mission control, the order everyone had hoped never to hear was given - the doors to the control center were locked, communications lines closed, and the process of recording the data from the flight began.

In the aftermath, a commission was set up to examine what went wrong, both in terms of the accident, and the procedures that had created it. One of the commission's members was physicist Richard Feynman. Were other members of the Commission met with NASA and supplier top management to understand the problem, he went in a different direction. He instead sought out the engineers and technicians, who were able to tip him off as to the issue with the O-rings. Whilst part of a televised hearing, he demonstrated how they would fail at very low temperatures by putting a sample of the material in a glass of ice water. In his own conclusions, he noted that the estimates for the reliability of the Shuttle were vastly different to those of the engineers who designed and maintained it.

His conclusion summed up the issues neatly:

For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled

Politics and Change

In the aftermath, NASA was able to secure funding to replace Challenger, with the new Endeavour. This was going to be required if the project to put up another space station was to continue. However, whilst this was given, the US interests in space were being examined closely. Projected costs for Freedom kept increasing, whatever design was put forward.

Meanwhile, Mir was growing. The second module, and the first to expand the station went on in early 1987. Kvant-1 was designed for astrophysics experiments, with a variety of telescopes, an X-ray/gamma ray detector and other parts. This was followed by Kvant-2 in November of 1989, shortly after Voyager 2 flew by Neptune. Also in 1989, the Soviet Union noted the passing of Valentin Glushko. The man who had for so long played second fiddle in the Soviet internal power struggle in the space race, and who's engines had been so instrumental to powering Soviet space vessels, died in Moscow, aged 80. His role at Energia was taken up by Yuriy Semenov, who'd continue until 2005.

The following year would mark the next leap forward for space exploration. The end of May 1990 saw the Kristall technology module added to Mir, but the real event had happened a month earlier, when NASA launched a piece of equipment which would produce some of the most striking and recognisable images of space ever produced.

Back as far as 1966, when von Braun was still alive and active, NASA had launched the first Orbiting Astronomical Observatory (OAO) mission. Whilst it died after just three days, its replacement OAO-2 worked from 1968 to 1972, three years longer than intended. As work continued and the vital role of space-based astronomy became apparent, funding had started to be gathered for a much more powerful device. The problem was, the proposed cost, which was (no pun intended) astronomical. In 1974, unsatisfied with the apparent projected costs, Congress pulled all funding for the project. It was only after serious lobbying by the scientific establishment, and the agreement to cut the scale of the proposed device, that funds were made available again. Even then, they were only half what was needed.

As a result, the newly established European Space Agency was contacted to see if they'd be interested in a collaboration. The ESA agreed, planning to provide funding and the solar cells required to power the telescope, in exchange for a guarantee of time allocation once it was in space. In 1978 funding was approved, with a projected launch date of 1983. The future telescope was named "Hubble".

Construction proceeded apace, but not altogether smoothly. Two years later, the project was already 30% over budget and three months behind schedule. And then there was the Challenger disaster. Work on the US space program shuddered to a halt, with the entire Shuttle fleet grounded. Hubble was now complete though, and powered up ready to be launched. To keep the delicate instruments from damage, the team kept it in a clean room, filled with nitrogen and powered up, until it could be launched. The operation to keep it ready cost an eye-watering $6 million a month. The delay was useful though, as the team hadn't yet actually written the software to make the telescope work. In the following four years, they worked to get it ready.

The shuttle program resumed flights two years later, in 1988, and in April of 1990, Discovery took to the skies to place Hubble in orbit. It had been planned to cost $400 million. Instead, thanks to over-runs and the delays in launching, it had cost over $2.5 billion.

Things weren't right though. As the team pointed their new toy and waiting to see what images it would return, it quickly became apparent that something was very wrong. The telescope didn't seem to be able to focus properly. Analysis of the flawed images it sent back revealed that the primary mirror had been ground to the wrong shape. Although even in its current state, it was still likely the most perfect mirror ever made, it was still too flat by 2.2 micrometers (millionths of a meter). This tiny distortion was catastrophic.

Back in the Soviet Union, things weren't much better. The Buran program, which had seen its only flight (and even that was unmanned) at the tail end of 1988 was being downsized. The Soviet Union itself was finally collapsing. 1988 had seen the Caucasus erupt in civil war, and various areas started to rise up, demanding autonomy. 1989 saw 2 million people join hands, forming a human chain stretching 600 km (370 miles) across three countries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania). A year later, with political power waning and lacking any real ability to keep the Union together, Moscow allowed all fifteen republics open elections. Six turned away, breaking the Soviet economic and political will further. Finally, in 1991, the entire thing came crashing down. Between August and December, 10 republics declared independence. In a nationally televised speech on Christmas morning, 1991, the final President of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev resigned, stating:

Dear fellow countrymen, compatriots. Due to the situation which has evolved as a result of the formation of the Commonwealth of Independent States, I hereby discontinue my activities at the post of President of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

He declared the office no more, and cede powers to Boris Yeltsin. The same day, Russia's legal name changed from "Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic" to "Russian Federation". It was now a sovereign state, on its own. That night, the Soviet flag was lowered for the last time, taken down, and the Russian tricolor raised in its place. The Soviet Union which had fought so hard for the moon, and for progress in space, was no more.

Hubble Triumphant

In NASA, the broken Hubble was problematic, but not awful. There had always been plans in place for servicing missions, so the team did the best they could for three years while they waited. Finally, in December of 1993, the optics were repaired by five EVAs with shuttle mission STS-61, conducted from the new Endeavour, which had had its maiden flight just a year before.

In January, NASA declared the mission a complete success.

The following period of operation, and the sights Hubble would unveil would mark the start of a period of astronomy unmatched in both the beauty of its images, to say nothing of the value of the scientific output. The bus-sized telescope would look back to the start of the universe, and forwards into its future. Through Hubble, the world watched comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 collide with Jupiter in 1994; the first time such impacts had been observed. It imaged galaxies billions of lightyears away, watched the first predicted reappearance of a supernova, and imaged the birth of stars in the Pillars of Creation.

Further, it demonstrated incontrovertibly the value of the Space Shuttle. The dramatic craft scored another PR win in 1995, when for the first time, the US Space Shuttle Atlantis docked with Russian Mir Space Station. By this time, the Buran program had been cancelled, amidst a pained Russian economy. Further, the Baikonur Cosmodrome, not being located in Russia, forced the new country to sign a lease with Kazakhstan, allowing continued use of the site.

The ISS Takes Flight

The latter half of the final decade of the 20th century saw the Pathfinder mission, consisting of a relatively cheap rover called Sojourner launch and land on Mars. The first planned project from NASA's Discovery Program (although the second to launch), the Discovery project's motto was (and remains) "cheaper, faster and better". During its operation, it would go on to take 16,500 pictures and make 8.5 million atmospheric measurements, as well as conducting analysis of the Martian soil and rocks. The entire mission cost less than a single shuttle launch, and continued the tradition of the various space probes, demonstrating the increasing ability of rovers and unmanned machines to do what people couldn't.

Back on Earth, a debate had begun to heat up. With Freedom's projected costs becoming eye-wateringly high, a solution was needed. In the spirit of co-operation, the Americans went to the Russians in secret, to discuss what could be done. The Russians initially suggested that the Americans join them in extending Mir. The US team thanked them politely, but expressed that this wasn't exactly what they had in mind. The second offer was that America fund a Russian program to build a space station for the US. This was, unsurprisingly, rejected as well.

Finally, they discussed the idea of a joint space station. The early components, including life support systems, propulsion and emergency escape vehicle would all be of Russian design and construction. Other components would be built by a consortium of international countries, with modules coming from America, Japan and the European nations. It would mark the end of space as something to be grasped for by a nation, and the start of a new, internationally co-operative era. Thus in 1998, 15 countries met in Washington to sign their support for the framework for the design, development, operation, and ongoing running of the International Space Station.

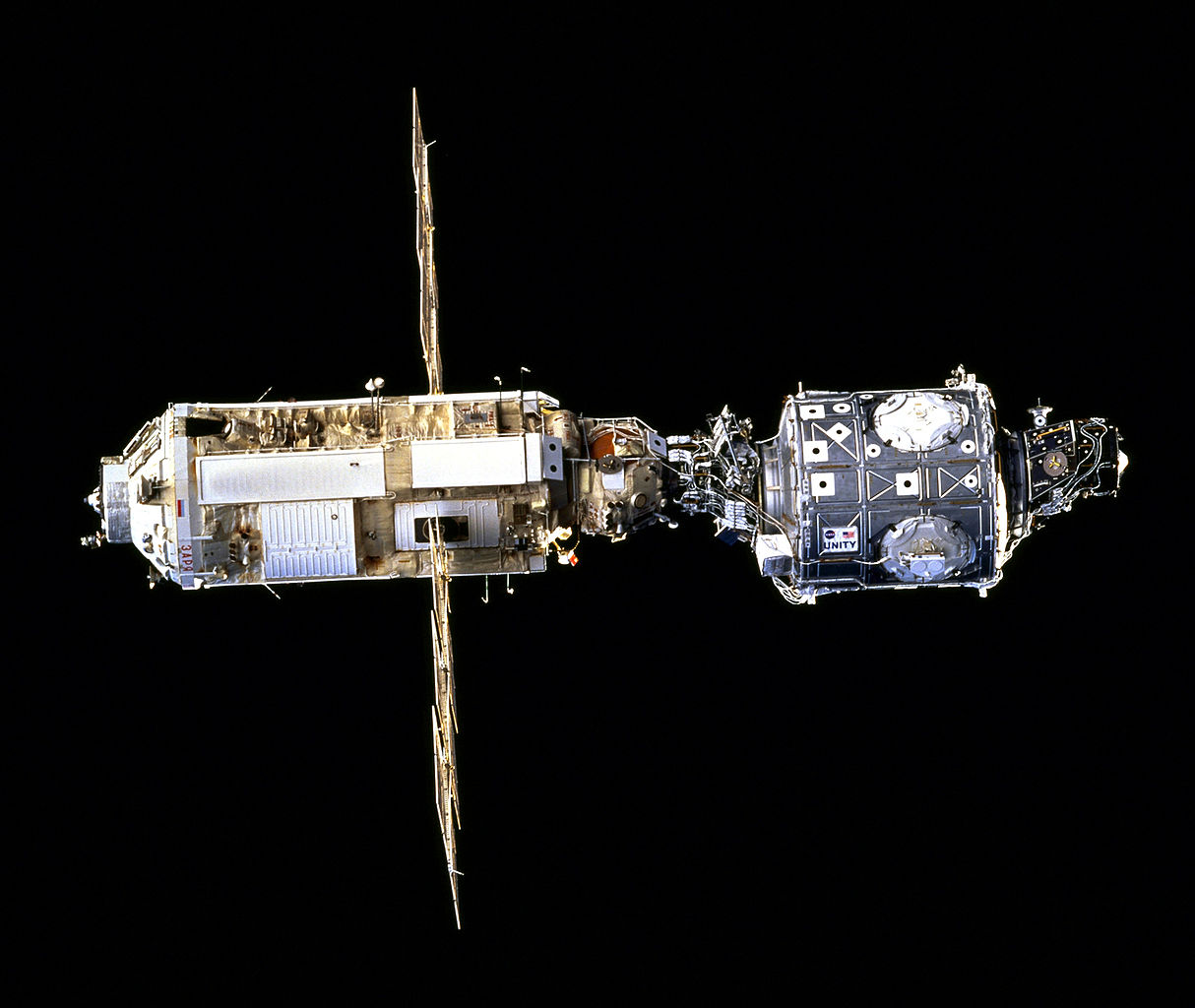

The timing was perfect. The Russians had been planning Mir 2, but hadn't the funds to complete such a project, let alone to run both it and Mir. Further, whilst the Americans hadn't yet invented technologies for solving many of the challenges faced with running a space station. Their focus on the Apollo and Shuttle programs had left them to fall behind, whilst the Russians had been running stations for years. The Russian team launched the first part in November 1998, named Zarya, meaning sunrise. Weighing over 19 tonnes, it was blasted in to space atop a Proton-K rocket. Two weeks later, the Space Shuttle arrived with the second module, named Unity. The creation of the ISS had begun.