Man in the Heavens

Putting a man in space and the start of the space race

With the arrival of the age of the satellite, both the USSR and United States had set their sights on the next goal: putting a man in space and bringing him safely back home. To the man on the street, it must have sounded like something out of science fiction. Certainly few would have believed you if you'd said it would happen inside of ten years. Putting an object in orbit is one thing, but making a vessel able to carry a man, keep him alive with the vacuum of space only kept back my the thinnest of sheets of metal, ensuring survival not just going up and in space but also through reentry, and returning him to Earth without the end of the journey killing him too. It was a massive step beyond anything that had been tried before, and both countries knew it.

More than that, any man who's going to accept such a mission must be highly trained, completely loyal, and understand he may well not return. He needed to have what would become known as "The Right Stuff".

In the US, the Americans were busy finding their people. President Eisenhower insisted that all candidates be test pilots of no taller than 5' 11" (180cm), weighing no more than 12 12lbs (82 kg), under 40 years old, hold a Bachelor's degree or similar, and have logged 1,500 hours or more of flight time. The newly created NASA searched for people who met all the requirements given, and identified in total 110 pilots who fit the bill. 69 were brought to Washington DC in two groups, but due to the level of interest from them, the final 41 were never asked to submit themselves for evaluation. Some of those may well have felt themselves lucky after they discovered what the prospective astronauts had to endure. Candidates had to spend hours on treadmills and tilt tables, allowing the doctors to measure their cardiovascular systems and resistance to motion sickness, as well as having their feet were placed in buckets of ice water for lengths of time, to say nothing of receiving a series of enemas. 39 failed or dropped out before or during the first phase of exams, and more refused to take part in the second round of tests. In total, just 18 made it through.

From a nation of 157 million, just seven men were finally chosen. Each had excellent mental and athletic abilities, and were considered the best for the job. They were Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, Alan Shepard, and Deke Slayton, known collectively as the Mercury Seven.

NASA finally introduced their future astronauts in Washington on April 9 1959. Although internally Project Mercury was planned simply to test the if humans could be sent to space and returned safely, the concept of American men in space electrified the nation. They were instantly seen as dare-devil explorer heroes, with TIME magazine going so far as to compare them to "Columbus, Magellan, Daniel Boone, and the Wright brothers." Two hundred reporters overflowed the room used for the announcement, and upon the meeting's conclusion, gave rapturous applause.

In Russia meanwhile, secrecy was everything. Those being interviewed to be the nation's first cosmonauts weren't told who they'd be working for, or even what they'd be doing. The Vostok programme's selection criteria is at once both detailed and focused, as well as abstract and vague. Potential cosmonauts had to be qualified Air Force pilots, to better cope with the extreme g-forces likely to be experienced, intelligent, physically fit, mentally resilient, male, between 25 and 30 years of age, no taller than 5' 7.5" (175cm) and no heavier than 11 5lbs (72kg). Their tests were similarly arduous, exposing candidates to extreme low pressure, high G in a centrifuge and more. Unlike NASA's astronauts however, the Soviet group were less experienced aviators. The Soviet R-7 relied on more automated operation in flight than the American systems at the time, which allowed for a greater initial selection pool.

Finally, the group was whittled down to just six men, who'd become known as the Vanguard Six: Yuri Gagarin, Valerij Bykovskiy, Grigoriy Nelyubov, Andriyan Nikolayev, Pavel Popovich and German Titov. Initially two other men, Anatoli Kartashov and Valentin Varlamov had also been on the team, but during training Kartashov suffered an injury in a centrifuge, and Varlamov injured his spine in a diving accident. They were replaced by Bykovskiy and Nelyubov, and training continued.

Whilst the focus on both sides was on selecting men for space, progress was being rapidly made in the realm of satellites. Vanguard 1 (which still remains orbiting in space some 56 years later) had been launched in March of 1958, along with Sputnik 3 in May. From there on though, only the US would continue attempting to put satellites in orbit, with a further 14 launches before 1960. Their record was patchy to say the least however, with no less than nine failing to greater or lesser degrees, including several resulting in the complete destruction of the rockets and payloads involved.

The idea of consistent, safe spaceflight was still very much a dream. The thought of launching human payloads shortly must have seemed implausible to say the least.

A Scientific Outlet

The Cold War had continued to intensify, but the public interest in the developing space race had given both sides an outlet - domination of space, and of each side's scientific teams had created a way for each side to show its own capabilities, outside of the military domain.

The men chosen to go to space were undoubtedly capable, on both sides. But it must have been a reminder that there was a good chance they'd be killed, every time they watched a rocket test, and it ended in disaster. And this wasn't a rare event - after watching an Atlas ICBM explode shortly after launch, Grissom remarked "Are we really going to get on top of one of those things?". With the ongoing failures of the Atlas systems, NASA started to look back to an old friend - Wernher von Braun. Von Braun had developed the Redstone missile, also capable of putting a man in space, and the vessel which had put America's first satellite into orbit. The Redstone was hobbled by two serious problems though: firstly it was designed as an ICBM, so it wasn't capable of carrying a passenger and keeping them alive (and even after modification to be able, would be deeply uncomfortable), and unlike the USSR's R-7 rocket, the Redstone was only barely capable of reaching space.

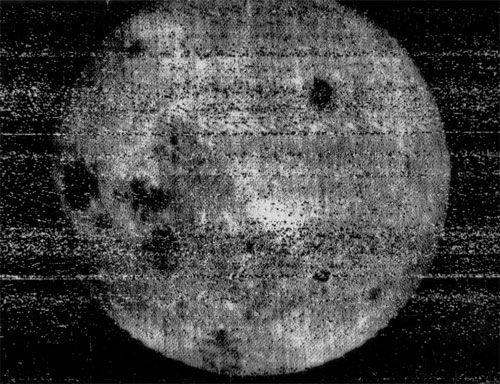

However, whilst von Braun was working to try and develop a version of the Redstone capable of manned flight, the Soviet team were powering ahead with other missions. They gained a massive political advantage when, on September 14, the Luna 2 probe impacted the Moon, east of Mare Imbrium near the craters Aristides, Archimedes, and Autolycus. In doing so, it not only became the first spacecraft to reach the surface of the Moon, but also the first man-made object to react a celestial body beyond the Earth. This was no little beeping thing like Sputnik either - unlike the satellite sent up less than a year earlier, this was a full scientific device carrying scintillation and geiger counters, a magnetometer, Cherenkov detectors and micrometeorite detectors. The timing was impeccable. The leader of the USSR, Nikita Khrushchev was in America when the news broke. Just three weeks later, another Soviet probe, Luna 3, will swing around the far side of the moon and took the first photographs of it.

Whilst the Soviets forged ahead, things were only getting worse for NASA. It had emerged that the Mercury capsule wouldn't fit on the Redstone rocket, and the project, almost a year behind schedule already, was slipping further. Things were not going well for von Braun, but his problems were mirrored by his Soviet counterpart, Sergei Korolev. For all the success Korolev was having with his R-7 derived Luna rockets, the Soviets were looking in to using a separate system, built by another team. To counter this threat, he created a plan for an audacious mission: the first to take a living creature to space and return.

After months of preparation and testing, on July 2 1960, a Vostok-L rocket with a Vostok-1K spacecraft carried two space dogs, named Chayka and Lisichka launched to attempt to put the first crewed vehicle into space. Sadly, 28 seconds into the flight an explosion destroyed the spacecraft. Undeterred, the Soviet space machine ground on and the next mission, designated Korabl-Sputnik 2, was launched merely weeks later, on August 19 1960. That time, things went somewhat more smoothly and two dogs named Belka and Strelka, along with a variety of mice and insects became the first living beings recovered from orbit, having been to space.

It was another huge win for Korolev's team, and for the Soviet's propaganda machine. More though, it was conclusive, incontrovertible proof that the USSR could send a man into space. With a ship that didn't need a pilot, just someone along for the ride, it was now just a matter of time until the USSR put a man in space. Meanwhile, America hadn't even yet managed to get a crewed vessel off the ground.

Attempting a launch test of the Mercury-Redstone 1 on November 7, last minute problems caused an abort to be called. The flight was rescheduled for the 21, and at 09:00 local time, the rocket fired, rose a few inches, and then immediately landed again, after which the capsule's escape rocket jettisoned itself, leaving the capsule behind. Then, three seconds later, the capsule itself deployed its drogue parachute, along with the the main and reserve parachutes moments later, ejecting the radio antenna in the process. The only thing that had been successfully launched was the escape rocket, which wasn't supposed to have done anything. Now though, there was a bigger problem: the active Redstone, with its full compliment of fuel, was now sitting on the launch pad with nothing whatsoever securing it.

Suffice to say, this wasn't to plan.

Fortunately, good weather conditions allowed the flight director Chris Kraft to make the decision to simply leave it. Over the next day, the batteries ran down, and the oxidiser boiled away into the atmosphere. The failure and subsequent panic in the control room led Kraft to declare:

That is the first rule of flight control. If you don't know what to do, don't do anything.

A young procedures officer named Gene Kranz dubbed it the "four inch flight". Whilst NASA were learning, they were lagging behind.

Mounting Tensions and Soviet Disaster

In 1960, amid mounting tensions, things suddenly took a turn for the worse. On 1 May, 15 days before the the East–West summit conference in Paris was set to begin, Captain Francis Gary Powers, flew from the US base in Peshawar in a U-2 spy plane, on a mission to overfly the Soviet Union, photographing locations including ICBM sites at the Baikonur and Plesetsk Cosmodromes, before land at Bodø in Norway. He was shot down near Kosulino, in the Ural Region, by the an SA-2 Guideline (S-75 Dvina) surface-to-air missile. He was captured soon after parachuting safely down onto Russian soil. His capture was a political nightmare. President Eisenhower was left with two choices: he could take responsibility for the U-2 flight, and in doing so destroy his credibility for the Summit in two weeks, or deny any knowledge, and appear politically impotent, with a government acting behind his back.

Against this backdrop of increasing belligerence on both sides, development continued apace. Despite the setbacks the Americans were having though, true disaster wasn't far away for the Soviets.

In October 1960, the Soviets suffered a series of catastrophic setbacks to their aerospace and nuclear experiments. The worst of these undoubtedly came on the 24, at the Tyuratam base, near the Baikonur Cosmodrome.

The Soviets were preparing for the first trial of the R-16, a completely new rocket designed to carry nuclear payloads. It was eventually to prove vastly superior to the existing R-7 design. Marshal Mitrofan Nedelin, the Commander of the Strategic Rocket Forces was the head of the program, and had commanded that all the members of the State Commission were present for the test. Others present included Mikhail Yangel, one of the leading Soviet missile designers, who'd had ambitions to challenge Korolev as leader of the Manned Space program.

The launch had been suffering a series of setbacks though, the test was repeatedly delayed. The first stage ignition had not fired successfully. Nedelin therefore demanded an immediate fix.

Frustrated at the continued delays, and feeling annoyed with the continual failure to launch, Nedelin left the command bunker and sat on a wooden chair at the foot of the rocket, surrounded by his senior staff to observe the final preparations. This was a gross violation of procedure, and put both himself and his team in grave danger. There was no opportunity for questioning the orders given though, if only because of the presence of the KGB agents on-site who had been tasked with ensuring the orders given were carried out.

It was to prove a fatal error in judgement.

A short circuit in a replaced component caused the second stage engines to fire while the rocket was still sat on the pad. Those engines sat over the vast, and nearly fully fuelled main stage. The second stage had just become the world's largest blowtorch, the engines' exhaust blasting into the main stage fuel tanks. Inevitably, the fuel detonated.

Nedelin was killed, along with 91 senior officers and engineers. Yangel and a test range commanding officer only survived as they had gone to smoke a cigarette behind a bunker a few hundred yards away, mere moments before.

Man Steps Beyond Earth

Back in America, the organisational structure at NASA for what would become the Apollo missions was starting to take shape. On February 14, 1961, James Webb accepted the role of Administrator of NASA. Meanwhile, von Braun was dealing with a difficult decision.

On January 31 1961, the American team had launched Mercury-Redstone 2 with Ham the chimp on-board. Issues with the flight however forced a choice to be made: fix the problems found and test the vessel again, or launch the next rocket with a man on board, knowing that serious problems might publicly kill the astronaut.

The decision was made that it was too risky. Another test would be conducted first. NASA had already decided who they'd send: a young test pilot by the name of Alan Shepard would be the first American to pilot the rocket and become an astronaut. He'd have to wait a little while longer though.

Meanwhile, the Soviet team had chosen who they were to send. Yuri Gagarin was well liked by his fellow cosmonauts, and by his superiors. With Gherman Titov and Grigori Nelyubov as backups, he would be the first choice to send.

Korolev however had other issues. Whilst he had the man to fly, he wasn't yet ready to send him. There were still lingering issues with the rocket. The question now was, which would be ready first - the Soviet rocket, or the American?

In the end, the Vostok 1 was prepared first. Because of weight constraints, there was no backup retrorocket engine to help the vessel descend. Instead, to mitigate against the risk of the retrorockets failing to fire, the spacecraft was loaded with 10 days of provisions to allow Gagarin to survive while the ship's orbit decayed. That however was just one of a hundred issues. For example, during the pre-launch preparations, it was decided to paint "СССР" on Gagarin's helmet in large red letters. It was still less than a year since Powers had been captured, and there was a fear that when he landed, local police could mistake Gagarin for a foreign agent, parachuting from an aircraft. The concern was so great about the vessel that some have rated the chances of success at just 50%.

Nevertheless, on April 12, 1961, 09:07 local time, Yuri Gagarin and the Vostock 1 took flight. Just three minutes later, the rocket reached 17,500 mph, the speed required to leave Earth's gravity. Then, a mere seven minutes later, Gagarin was able to look out the window, and having become the first human to experience weightlessness, and float in a man-made vessel, in space. Two hours later, he'd have returned, having flown entirely around the world, across the edge of the sleeping South America, and landed back on Earth, around 170 miles (280km) from Baikonur.

One can only imagine what went through the minds of the farmer and her daughter who discovered the world's first cosmonaut, watching Gagarin in his bright orange cosmonaut suit and large white helmet approach them after landing nearby. He later recalled:

When they saw me in my space suit and the parachute dragging alongside as I walked, they started to back away in fear. I told them, don't be afraid, I am a Soviet citizen like you, who has descended from space and I must find a telephone to call Moscow!

One Place Left to Go

The Americans, used to being second by this point, send Alan Shepard less than a month later. In contrast to the Gagarin's flight, Shepard's lasts 16 minutes, and travels just 300 miles. He was weightless for 6 minutes, and with the much less powerful Redstone rocket, was incapable of reaching orbit. It was enough to allow America to say they'd also put a man in space, but they needed a much bigger win.

Prior to Gagarin reaching space, now US President John F. Kennedy hadn't been a particularly large supporter of the American manned space program. Having only been in the job for just over three months, it was a shock to be woken up, and told that the Soviets had managed what NASA had not. Just the previous month, NASA administrator James Webb had submitted a budget request to fund a Moon landing , aiming to be there before the end of the decade. Kennedy however rejected it, believing that the costs involved were just too high. He also had one eye on Vietnam and Laos, as well as the situations in Europe and Latin America. Indeed, in his inaugural address, he'd pledged to:

...pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and success of liberty.

Gagarin's flight forced his hand though. In light of the success of the Vostok 1 mission, Kennedy knew how the American public would respond emotionally. The sense of humiliation and fear was palpable. Seeking advice, he tasked the new Vice President, Lyndon B. Johnson with assessing the state of America's space program, and how NASA could rapidly advance and respond. The two options proposed in response were the establishment of an orbital space station, or putting a man on the Moon. Only those would carry the gravitas required to allow the American public to see itself as putting the Soviets back in their place. Johnson therefore turned to von Braun, who gave his estimates on the feasibility of each. Johnson brought the answers back to Kennedy, concluding that a manned Moon landing was difficult enough that neither side could currently achieve it, and that if they made it their sole aim, that the US could potentially beat the Soviets to the punch.

Kennedy took Johnson's advice, and launched what would become the Apollo program. He justified the colossal expenditure by emphasising the importance to national security and putting focus scientific and social endeavours. Now all that was left to do was to reassure the American people that all was in hand. So it was that the world watched in wonder in autumn of 1962, as John F. Kennedy spoke at Rice University on September 12, announcing America's response. In no uncertain terms, the US laid down the gauntlet: they were sending men to the moon. The Soviets were welcome to beat them to it, if they could.

We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theatre of war. I do not say that we should or will go unprotected against the hostile misuse of space any more than we go unprotected against the hostile use of land or sea, but I do say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours.

There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful cooperation may never come again. But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?

We choose to go to the Moon! We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.

Back to part 1: The Race to Space

Continue to part 3: The Challenge Set